by Maurice Y. Michaud (he/him)

As I explained in the introduction to this section, for several decades in all jurisdictions in Canada, the decennial redrawing of the electoral map is done not by politicians or the legislature, but by an independent non-partisan commission in each province or territory. At the federal level, once Elections Canada has determined how many ridings a province will have, it creates such a commission in each province so that the detailed work can be done by people who know the province well, as this process is not as simple as chopping up the province into x slices and ensuring that each riding has the same number of people.

As I explained in the introduction to this section, for several decades in all jurisdictions in Canada, the decennial redrawing of the electoral map is done not by politicians or the legislature, but by an independent non-partisan commission in each province or territory. At the federal level, once Elections Canada has determined how many ridings a province will have, it creates such a commission in each province so that the detailed work can be done by people who know the province well, as this process is not as simple as chopping up the province into x slices and ensuring that each riding has the same number of people.

But before we get into that, let’s take a step back and consider how the number of seats is determined in the first place. Let’s compare how it’s done in the United States and Canada, as that is where we find the first of two fundamental differences in the apportioning process between the two countries.

Both the United States and Canada have adopted the principle of representation by population for their lower house. The theory and the intention are to ensure that the vote cast by someone in a rural region at one end of the country carries roughly the same weight as the vote cast by someone else in an urban region at the other end of the country.

For the United States House of Representatives, the decision was made by the 1850 census to have a “fixed house size” and to apportion seats to each state in proportion to its population, although that fixed number was increased as more states entered the union. Over time, an adjustment clause had to be introduced to prevent states with a very small population, like Wyoming or Vermont, from being apportioned no seat. Since the admission of New Mexico and Arizona as states in 1912, that number has been fixed to 435, except for a temporary increase to 437 in 1959 when Alaska and Hawaii were admitted as states, a year before the next decennial census. As a result, as the population of the country increases, so does the number of people who are represented by a single seat.

In Canada, the first House of Commons had 181 seats when it grouped New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and the United Province of Canada — Canada West (formerly Upper Canada) which became Ontario, and Canada East (formerly Lower Canada) which became Québec. That number of 181 — 65 for Québec, 82 for Ontario, 19 for Nova Scotia, and 15 for New Brunswick — had been arrived at by dividing the population of each province by a fixed quota referred to as the “electoral quotient,” which itself had been determined by dividing the population of Québec by 65, which was the number of seats Canada East had in the Parliament of the Province of Canada.

Like in the United States, seats were added as new provinces joined the federation, and four seats were granted to the North-West Territories by the 1887 general election, even though that large area had been formally part of Canada since 1870. By the 20th century, as the population of the country grew rapidly, the decision was made to keep adding seats in order to maintain a reasonable electoral quotient — that is, the number of people who are represented by a single seat.

The provinces have followed the same reasoning as the federal government’s, except Manitoba which has set its number of seats to 57 in 1949 and has kept it there ever since, and Prince Edward Island which has had a stable number between 27 and 32 for nearly two centuries. Thus those provinces have adopted the American approach. But as a rule, the trend has been towards an increase in the number of seats, although there have been times when the number has gone down. However, and interestingly, the most pronounced pushes downward have occurred in recent times.

That might seem like a silly or redundant question to anyone who is 55 years old or younger. But that’s only because you have always voted using the first-past-the-post electoral system. So if you happen to have turned 55 this year, ask yourself how many times lately have you been able to plead innocence due to your youth?

Indeed, the clue is in the name of the system itself: the first ONE who gets to the finish line WINS — emphasis on the singular. Arguably, the plurality-at-large or “block” system is a variation of FPTP, except that there are x seats to be won in the riding. In fact, the FPTP system is the only one that can only have a 1:1 ratio — one riding, one seat. So for the young’uns reading this — those 55 or younger — you’re excused for saying interchangeably, “She won the riding” or “She won the seat,” although the latter is more accurate.

So how many ridings are there? Today you could answer, “The same as the number of seats.” However, if the electoral system were to change, the answer could be, “Fewer than the number of seats.” But the answer would never be, “Greater than the number of seats.”

If my answer just confused you, you might want to play with the search engine found in “In numbers.”

Neither way is better nor worse. Both adhere to the principle of representation by population. Both require some tweaks at the federal level to accommodate provinces or states with a very small population. With one, the number of seats is fixed, while with the other, it tends to go up. So it’s a choice between setting a limit on either the number of seats in the house or the number of people represented by one seat in the house. The United States have chosen the former while Canada has chosen the latter. But it is nothing more than that: a choice.

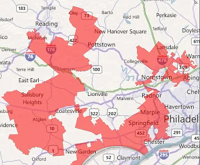

Then, somebody has to take that number, get the data from the latest census, and start drawing lines on the map. And that is when, compared to Canada, the United States fall flat on their ultra-partisan face. There, it’s done by each state’s legislature. And neither party — Democratic or Republican — has ever hidden the fact that one of their biggest motivation for controlling a state house is to be able to redraw the electoral map to their party’s advantage.

That is what gerrymandering is. And no, that no longer exists in Canada.

I think I can hear some of you say, “Wow, Maurice! You sound very confident in saying that! But didn’t you mention a great example in Ontario a few paragraphs back?”

Well, that was not gerrymandering. Each province has the right to legislate on how many seats it wants to have in its legislature. But that legislation still has to be constitutional. It is not like, in the Ontario case, the legislature had appropriated from Elections Ontario to itself the right to draw the actual map, or done away with the principle of representation by population. If anything, they made the life of Elections Ontario workers easier by telling them, “Let the federal government do all the work and then just go with that.” Besides, aside perhaps from Québec, Ontario, due to its imposing demographic weight within the federation, is the only province where the thought of using the federal map could even be considered. Don’t hold your breath waiting for British Columbia to go from a 93- to 43-seat legislature, or Nova Scotia from 55 to 11.

I have to admit that I’m a bit astonished that I just defended a piece of Harris government legislation! However, I’m not saying that it was a good or a bad idea — just one that was defensible and that it was NOT a case of gerrymandering. Interesting fact to note: the following Ontario Progressive Conservative government chose not to align its electoral map with that of the federal government for the 2025 general election.

Moncton Centre or Moncton South?

Moncton Centre or Moncton South?

I’m reposting here the image from the top of this page, which is the map for the provincial riding of Moncton Centre as created in New Brunswick’s 2022 redistribution, to illustrate how difficult the job of the commissioners can be. Take note in particular of the downward bump in the southeast, and specifically the upper horizontal line in that bump. That happens to be the street where I grew up and where my mother lived until she died. If she were still there and willing or inclined to vote, she would be voting in Moncton Centre. But the people living directly across the street from her would be voting in Moncton South, which includes Moncton’s downtown area.

Because at some point, the commissioners simply have to draw the line. Pun intended. That little southeast bump may have pulled in just enough people to achieve the right proportion of voters compared to the other ridings. And although I can only speculate, the facts the commissioners may have had to consider could have been that:

Westmount—Ville-Marie, Mount Royal, or Outremont?

It’s like the first apartment building where I once lived in Montréal. The building is at the corner of two major streets. Federally, those of us on the south side of the street voted in Westmount—Ville-Marie, while our neighbours across our street voted in Mount Royal, except those on the northeast corner who voted in Outremont. All because, at one point, the commissioners simply had to draw the line. Pun intended.

Again I can only speculate, but I suspect the commissioners’ biggest consideration in recent decades (both federally and provincially) when it comes to Montréal has been how the number of people living in the metropolitan area has kept growing, but that metropolitan area itself has been extending much further north and south ("Couronnes nord et sud" in French, or North and South Shores in English), leaving relatively fewer people living on the Island of Montréal. So I can see how, over time, an area of the Island that was represented by two ridings can evolve to, say, three-quarters of that area being represented by a single riding.

Moncton—Dieppe or Beauséjour?

Back in my hometown of Moncton, but at the federal level, the city had grown so much by 1968 that it was separated from the riding of Westmorland to stand on its own. From 2000, it encompassed the entire metropolitan area and was renamed Moncton—Riverview—Dieppe. As a result of the population of the area continuing to grow, there will be, as of the 2022 redistribution, a geographically smaller riding to be known as Moncton—Dieppe. The bedroom community of Riverview, which is directly across the Petitcodiac River from Moncton, will be on the eastern edge of Fundy Royal, which extends all the way west to the outskirts of Saint John (about 120 kilometres away), while only half of the city of Dieppe will actually be part of Moncton—Dieppe, the other half needing to be placed in Beauséjour.

Some people from Dieppe expressed their dismay about this fact at the public hearings, as they would have liked to remain in “Moncton.” However, the simple fact is that the sum of the population of both cities is far greater than what should be the average of the 10 federal ridings in New Brunswick. Therefore, at one point, the commissioners simply had to draw the line. Pun intended.

Unlike in the United States, none of those lines were drawn with partisan motives. In that last example, commissioners were tasked with dividing the province of New Brunswick into 10 relatively equal ridings, within an allowed variance. It’s not an easy undertaking, as one can easily imagine the domino effect of each decision. But at least the whole process is deaf to partisan pressure from politicians.

Unlike in the United States, none of those lines were drawn with partisan motives. In that last example, commissioners were tasked with dividing the province of New Brunswick into 10 relatively equal ridings, within an allowed variance. It’s not an easy undertaking, as one can easily imagine the domino effect of each decision. But at least the whole process is deaf to partisan pressure from politicians.

And that’s good because I’m not convinced that politicians in Canada are any better than those in the United States when it comes to this issue. If given a chance, wouldn’t they try to pull crazy gerrymandering stunts like their American counterparts? Of course they would! They used to do it before the redistribution process was taken away from them. In Duplessis’s Québec of the 1950s, on the same electoral map that cartoonishly overrepresented rural areas, the riding of Laval had 135,730 eligible voters, while L’Islet had only 11,830. That kind of imbalance only makes sense to politicians. Impartial commissioners wouldn’t even come close to entertaining such a thought.

All that being said, are the commissions and the people who sit on them perfect? Of course not! That’s why they submit a preliminary report and hold public hearings before submitting their final report. People can come forward to point out flaws, like “That little area of the city over there has far more affinity with THIS side of the city than THAT side.” But it can be assumed that the commissioners, led by a judge, may have made such a mistake in good faith, not because of some kind of hidden political agenda.

Redistribution, when done well, is both an art and a science. It requires balancing numbers (population and how many ridings there should be) with the reality on the ground. When we say that a riding has been abolished, we understand that the affected area has not evaporated from the map (unless we’re talking about the Northwest Territories’ community of Pine Point, which closed in 1988). It simply means that the demography has changed and, as a result, the ridings have had to evolve along with those changes.

So as tempting as it might be for the citizens of the Island of Montréal or the Gaspésie region to scream “gerrymandering” when they see their number of seats diminish, the fact is that the population may have simply shifted away from those regions and has not increased significantly overall to justify adding new ridings. If we were to give in to those citizens’ demands and allow them to be overrepresented, how do you think the citizens of the other regions will perceive them? Cry babies? Entitled?

Okay, I won’t speak for you but only for myself... Yes, that’s how I perceive them! When I heard that municipal politicians from the Gaspésie region managed to get the National Assembly to pass a unanimous motion in May 2024 that suspended the redrawing of the map for the 2026 election, I saw red! As of April 2023, Bonaventure had 35,898 voters and Gaspé 30,131 voters, placing them respectively at 29.2% and 40.6% below the provincial average.* Alone, my riding of Mont-Royal—Outremont on the Island of Montréal, which would also be losing a seat, has 57,570 voters, or 87.2% of the sum of Bonaventure and Gaspé. That means that Madame Côté’s vote in Gaspé weighs nearly twice as much as mine. I’m okay with that for Ungava, with the same population as Gaspé but that covers more than 855,000 square kilometres, but not for Gaspé that covers just over 33,000 square kilometres. Or it it time to increase the number of seats in the National Assembly so that we can lower the electoral quotient? That’s what happened in the Yukon in 2024, when the commission initially recommended keeping 19 seats but giving more to Whitehorse, and when people voiced their concern, the commission increased the number of seats to 21.

That’s precisely the topic of next page of this section, namely taking a closer look at the mathematics of a redistribution and, in particular, how to come up with an electoral quotient that might reduce the butthurt of places like Gaspé.

* Nelson Sergerie, MaGaspesie.ca (5 December 2024), La Loi qui suspendait la révision de la carte électorale reste en place... pour le moment. (Retrieved 9 December 2024)

(Retrieved 9 December 2024)