Canada's electoral history from 1867 to today

An uninhibited, no holds barred argument for proportional representation

by Maurice Y. Michaud (he/him)

Not surprisingly, those who have never studied electoral systems nor looked as I have, without bias, at the results of all the elections ever held in Canada tend to opine freely but very superficially on the matter of electoral reform. I offer as evidence the comments section of this article that appeared on CBC News

Not surprisingly, those who have never studied electoral systems nor looked as I have, without bias, at the results of all the elections ever held in Canada tend to opine freely but very superficially on the matter of electoral reform. I offer as evidence the comments section of this article that appeared on CBC News  shortly after the 2015 federal election. Just as everyone suddenly seemed to become epidemiologists during the COVID-19 pandemic, we tend to assume that we know the minutiae of our electoral system because we all know how to cast a ballot. But, in fairness, I need to remind myself that, along with Éric Grenier and Philippe J. Fournier, I am probably one of the few Canadians who is crazy enough to have recorded and poured over all those results in detail — with apologies to Éric and Philippe for somehow suggesting that they are crazy, which they are not!

shortly after the 2015 federal election. Just as everyone suddenly seemed to become epidemiologists during the COVID-19 pandemic, we tend to assume that we know the minutiae of our electoral system because we all know how to cast a ballot. But, in fairness, I need to remind myself that, along with Éric Grenier and Philippe J. Fournier, I am probably one of the few Canadians who is crazy enough to have recorded and poured over all those results in detail — with apologies to Éric and Philippe for somehow suggesting that they are crazy, which they are not!

Although this may make me sound elitist and non-democratic, I agree with Dennis Pilon, the York University political science professor quoted in that 2015 article, that this matter of changing our electoral system should not go to a referendum. Did we get to choose the FPTP system we now have? Were we asked our opinion when multi-member districts were abolished from 1967 to 1991? Not at all, because those are really more admisminstrative matters. Although the formula for allocating seats in the House of Commons is part of the Constitution, it has been amended several times and we were not asked to vote on those amendments. Besides, the electoral system should not have an impact on the number of seats assigned to each province, plus let's not forget that each attempt at electoral reform in Canada in the 21st century that reached the referendum stage has failed because of misinformation and a lack of political will to make the initiative succeed. In fact, I suspect bad faith among those who oppose proportional representation when they insist on having the matter brought to the electorate. Under the guise of wanting to be democratic, they intend to use the referendum to sow confusion in order to ensure that we keep the current system.

However, as I mentioned in "Changing our actual system?" there are electoral systems that are worse than FPTP. Sorry for being simplistic, but any majoritarian system is bad. Period! Full stop! Instant runoff/Alternative voting is the worst, though, not because it is favoured by the federal Liberal establishment but because of math! While it is true that each person elected under this system can claim — thanks to some fancy mathematical scheme — that they obtained a majority of the votes in their riding, when the tally of the seats happens afterwards, the results are even more lopsided than under FPTP.

That is why we must be careful whenever the appetite to replace FPTP increases, as we could be at risk of changing for change's sake and making matters worse. However, perhaps what bothers me the most is that the Law Commission of Canada had already studied the matter in 2004 and came up with an excellent "Made in Canada" solution, so why did we try to reinvent the wheel in 2015? There are more ridings today than there were back in 2004 but the analysis and recommendations in that report were still valid. Alas, that important work, which we as tax-paying citizens had already paid for, was shelved after it was submitted — presumably because its proposal did not align with the preferred system of the party in power at the time, which, like now, whichever the party, would stand to lose a bit of power if the system were actually — by golly! — fair!

Despite their good intentions, even some who advocate for proportional representation, as well as some journalists who attempt to explain what PR would look like  , can simplify the argument too much. They only look at the percentages of the popular vote across the jurisdiction and translate that percentage into number of seats. Except Canada is a big country with extreme regional differences politically. Try finding a Green Party supporter in Newfoundland or a Liberal supporter in Fort McMurray... and I wish you good luck with that!

, can simplify the argument too much. They only look at the percentages of the popular vote across the jurisdiction and translate that percentage into number of seats. Except Canada is a big country with extreme regional differences politically. Try finding a Green Party supporter in Newfoundland or a Liberal supporter in Fort McMurray... and I wish you good luck with that!

Because you see: first, in 1993 and 2015, many voted Liberal "strategically" in those federal elections because of their intense loathing of the incumbent government — that is, even though they did not need to do so since they were already represented by a non-government member of parliament and the voting trends in their riding over the last 20 years did not suggest that would change, and as long as switching to the Liberals did not go completely against their political grain. (The example of the NDP's Megan Leslie in Halifax in 2015 comes immediately to mind.) As a result, the percentages of the popular vote for the main and even some minor parties were an aberration and not indicative of a sudden love affair with the Liberal Party. Secondly, if we had two votes — one for our local MP and one for our preferred party — we would not feel the need to vote "strategically." For instance, one could easily vote Liberal or Conservative locally but for the Greens (or whomever) on their party ballot.

Once the seats won by regular FPTP would have been counted (which would be the majority of them), then the popular vote by party would be examined. The parties that met the mimimum threshold, but did not perform as well in the FPTP races, would get "compensatory" seats to bring them closer to the popular vote they obtained. The final results would not be perfect and would only be as good as the system's design and the method used to allocate those remaining seats, but they would certainly be closer (and fairer) than any FPTP election could yield.

But I am more tired of opponents' simplistic or partisan arguments against proportional representation. By "partisan arguments," I mean when someone cherrypicks examples of elections in which FPTP mistreated their party — for instance, their party won the popular vote yet it got fewer seats than the winner. But then they drop from their argument the times when FPTP worked in their favour. Is that because those latter cases were acceptable outcomes? I don't know if I'm tired of them simply because they bore me or, to paraphrase a great French expression, because their slip is showing, for if there is one thing I cannot stand, it's intellectual dishonesty!

We have some pretty colourful polemicists in Québec, but this one who happens to oppose PR  is particularly guilty of that sin. Juxtapose someone like him to Chantal Hébert, who, granted, is not a polemicist but calls the good and the bad shots by whomever, regardless of their political stripe, and never gives away her own political leanings even though we might suspect what they are, or more likely aren't. On the bright side, if the arguments of opponents of PR have holes big enough to drive a truck through them, then making the case for it should be easier as long as their lack of credibility can be made plain for everyone to see. So let's talk about their flimsy arguments — except Christian Dufour's, since his slip is not just showing; his entire outfit has fallen off and he is already embarrassing himself parading nude.

is particularly guilty of that sin. Juxtapose someone like him to Chantal Hébert, who, granted, is not a polemicist but calls the good and the bad shots by whomever, regardless of their political stripe, and never gives away her own political leanings even though we might suspect what they are, or more likely aren't. On the bright side, if the arguments of opponents of PR have holes big enough to drive a truck through them, then making the case for it should be easier as long as their lack of credibility can be made plain for everyone to see. So let's talk about their flimsy arguments — except Christian Dufour's, since his slip is not just showing; his entire outfit has fallen off and he is already embarrassing himself parading nude.

So without further ado, let's get to it!

- "PR would open the door to too many fringe parties."

- It's always about those weird-to-you outcasts, isn't it?

If you had been listening more closely, you would have heard that everyone agrees that the proportional systems in Italy and Israel are hot messes. The reason why the PR systems in all the other countries work is because they are designed with a minimum threshold to determine eligibility for compensatory seats. The majority of the seats — from 55 to 75 percent, depending on the system's design — are still won using the FPTP method you know well. So if a party happens to win one or two seats that way, a bit like how some independents succeed today, then good for them! But if overall they only obtained 4% of the popular vote, that's all the seats they will be getting this time. So:

- To those lucky elected members through FPTP: Congratulations and enjoy your seats!

- To those who oppose PR on these grounds: Your problem was? Oh, never mind... Problem solved!

A minimum threshold to obtain compensatory seats is the "magic" ingredient to make this PR recipe work. Without one, and had the 1993 federal election been held under an Italian- or Israeli-style PR system, by virtue of getting 84,743 votes nationwide (i.e., 0.62%) and 21 best finishes in fourth place, the loony Natural Law Party might have won a seat in the Commons. Can you imagine? But with a threshold of just 5%, given that 100% of the votes for the Bloc Québécois came from Québec but that the votes obtained by the Reform Party came from everywhere else, Reform would undisputably have been the Official Opposition in the House, while the Progressive Conservatives — who after all did get well over 2.1 million votes or 16% nationwide (or only 372,823 fewer votes than Reform) — would have been directly behind them with perhaps 49-50 seats instead of only 2, then followed by the Bloc Québécois. The following decade might have been less tumultuous on the right of the political spectrum and most factions might have kissed and made up well before late-2003.

It's because of this kind of vacuous argument that I believe this matter of changing the electoral system should not go to a referendum. We must deny opponents of PR the opportunity to indulge in groundless arguments so that we can expend our energy on demonstrating why PR is better and not a scam, which might take some convincing with a public whose cynicism towards politics can make them prone to falling for such easy, sensationalistic and spurious arguments. I say that not because I think the public is stupid; rather, I think most people have other priorities, lead busy lives and, as any political commentator worth their salt will tell you, do not pay as close attention to every twist and turn and pseudo or real scandal as they do in the "chattering class." I mean, I confess that I never read any political party's platform at election time, yet I would not refute being labelled a political junky! So it's on that premise that I am expressing the need to defend PR without the interference from silly partisan distractions that would inevitably come with a referendum.

- "Wait a minute... 'Compensatory seats?' You mean there would be more elected officials?"

- There is no appetite for bigger government.

Again if you had been paying attention, you would have heard that the PR systems that have been proposed in Canada in recent years suggest that the number of seats in the legislature would remain the same or be only slightly higher.

The electoral map would obviously need to be redrawn. The "local" ridings would be larger in order to have fewer ridings and voting in those ridings would still use the current FPTP system. But then, clusters of local ridings would form "regional" ridings, and the sum of all the ridings would be equal to the current number of seats. Therefore, people would have two votes on election day: local and regional.

Those regional seats would be the compensatory seats. They would be assigned to the parties meeting the eligibility threshold to correct the percentage gap, as much as possible, between the popular vote they obtained and the number of seats they won locally through FPTP. The fewer regions there are — the more ridings are clustered into a region — the better proportionality will be. So:

- To those who vote: You would have two representatives instead of only one, yet there would not be more people in the legislature.

- To those who oppose PR on these grounds: We actually agree that we do not need more elected representatives.

Some PR systems have actual "top-up" seats that are created to ensure perfect proportionality and then those seats are eliminated if they are no longer needed after the following general election. But our system does not have to be like that. We can aspire for a system that is simply more proportional than the one we have now which, when coming from the FPTP, is not that hard to do! And if one party happened to have been very successful and won most of the local races (and thus would not need compensatory regional seats), there might not be enough regional seats to completely eliminate the gaps for all the other parties, but at least the gaps would not be as severe.

- "Giving voters two ballots? No, no, no... They'll get confused!"

- Do you really think people are that stupid or is it just you?

There is nothing confusing about asking people to vote more than once. They are already doing it at the municipal level. Heck! I am in Montréal and municipally, where we actually have a party system, I have to vote for a city mayor, a borough mayor, and a councillor or two. It's not rocket science and all the research on electoral systems that I have done does not give me an edge over everyone else in grasping what I am asked to do! What's more, although we use the FPTP system, I can vote and have voted for different parties on different ballots. So:

- To those who vote: Don't worry, you'll be fine. You're already doing it.

- To those who oppose PR on these grounds: Don't worry, they'll be fine. They're already doing it.

This is by far the weakest argument that some opponents of PR try on, but since it gets dismissed very easily, they then try to tackle their "PR is too complicated" narrative from other angles.

- "Local seats. Regional seats. Assigning those compensatory regional seats... It all sounds so complicated!"

- Good thing you are not the one in charge of counting the votes! But seriously, let me tell you a little story...

When I was an undergraduate in what was essentially an arts program, I had to complete a full-year course in statistics. I was not horrible in mathematics, but I certainly did not consider it my strength academically and I was worried about being at a disadvantage because I had studied maths in French in high school and the program I was in was taught in English. Therefore, I was terrified of that course! I worried I would do badly or, worse, fail and have to take the course twice.

Then, a friend of my roommate at the time, who happened to be an engineer, gave me the best advice anyone could have given me. "Don't try to understand why a formula works," he said. "It's been tried and true and tested millions of times, plus you're not expected to memorize all the formulas. You just need to figure out which one you need to prove or disprove your hypothesis."

He was absolutely right. At each exam I was allowed to bring in one page on which I had scribbled down all the formulas we had learned. Thus the challenge was to figure out when and why I needed to apply this formula rather than that formula given the hypothesis that had to be demonstrated as "statistically significant" (or not) with the data that was given.

My final grade in statistics was 90%. I totally aced my dreaded stats course!

Sorry for the put-down about you not being the one counting the votes, but what I was trying to say it that it is really not that complicated — certainly less complicated than full-on stats! The only "complication" is that there would be two sets of votes to count instead of only one but that is not a big deal, especially in an era when we have as much if not more computational power in our hand with our smartphone than we had sitting on our desktop in 1992 — not that we would be using unsecured smartphones to count votes. Plus proportional elections, often with far more complicated counting schemes than the one I am arguing for, have been held around the world for decades, meaning way back when much of the tabulation had to be done by hand. So:

- To those who vote: If they can do it in Albania, Algeria, Angola, Argentina, Armenia — do you want me to continue? — Aruba, Austria, Belgium, Bénin, Bulgaria — okay, I'll stop! — we can most certainly do it in Canada, right?

- To those who oppose PR on these grounds: You are either making an effort not to understand or simply scaremongering.

We must get past our fear of the unknown. That which is unknown to us is in fact well known in many other countries. It is time for us to catch up with them.

- "Those bigger ridings will mean people will be less represented, especially in rural areas."

- That statement is simply not true — neither now nor when PR would be implemented.

Ridings (or electoral districts) are one area in which proportionality already exists, with exceptions granted for very isolated or large rural areas, in an attempt to meet the criterion of "One person, one vote." The idea and the ideal are to make each person's vote carry roughly the same weight no matter where it is cast.

It's important to remember that this notion did not always exist in Canada, for indeed, in the 19th and early years of the 20th century, only men 21 years of age or over who met certain land ownership criteria were given the right to vote. Universal suffrage was only granted federally in 1920, with some provinces like Manitoba granting it as early as 1916. By that I do not simply mean that women were finally allowed to vote, but that the ownership criterion was also dropped. Even there, Chinese Canadians were only granted the right to vote in 1947, and indigenous peoples in 1960. The voting age was lowered to 18 federally in 1970.

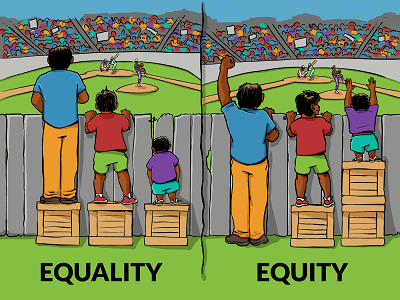

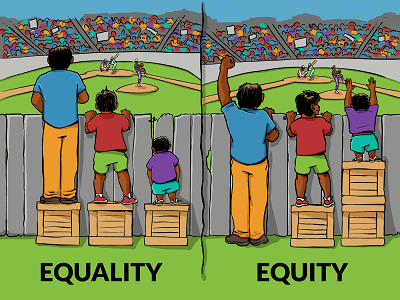

©

Photo

2016 Angus Maguire via Interaction Institute for Social Change — Fair trade

It is only by the early 1960s that most jurisdictions redrew their electoral map to redress this urban/rural unbalance. While one could take a map and coldly ensure that each riding has the same number of people, doing so would not take into account natural affinities between bordering communities. For instance, do the people of Leduc County, Alberta, relate more to Edmonton directly to their north or to the more rural area of Westaskiwin directly to their south? If Leduc, given the number of ridings that needed to be created, had to be included in one or the other, which would it be? Following the 2012 federal redistribution, it was decided, given to number of ridings alloted to Alberta, to place it in a riding that was named Edmonton—Wetaskiwin, but when the 2022 redistribution gave the province three more ridings, it could be placed in the new more rurual riding of Leduc—Wetaskiwin.

A population variation of x% is allowed to address this kind of dilemma, not to mention that there can be the notion of "protected seats" in some jurisdictions to respect significant historical and cultural minorities in some communities, as well as isolated areas which may have very few residents compared to their very large territory. Although in Québec it may make sense mathematically to merge Ungava with one of its neighbouring ridings to the south, pity the person who would have to represent that riding, which would cover even more thousands of square kilometres, and the people that person would have to represent!

So before Conservative supporters in the federal riding of Kenora (Ontario) start comparing their riding to the one in Québec that is held by the prime minister (Papineau) and complaining that they are underrepresented because "Québec, as usual, is always overrepresented," they should consider this. In the 2021 federal election, there were only 46,382 eligible voters in the Kenora riding which covers 321,741 square kilometres for the 72,972 eligible voters in the Papineau riding which covers only 10 square kilometres. The notion of equity has already been applied to Kenora because we, as fair-minded citizens, recognize the challenges faced by rural residents and those who represent them.

Therefore, to come back to your point: In addition to the efforts already made to ensure that rural areas are represented equitably, a PR system would then cluster the redrawn local riding of Kenora with other northern Ontario ridings to create a region for which one or more regional party seats would be assigned based on the popular vote. Depending on how the results in the local FPTP ridings played out, there could be additional regional Conservative members, or members of the Liberal Party, or the NDP. And let's say, for the sake of argument, that one of those regional seats went an NDP member because that party came a relatively close second regionally yet did not win any local seats in the region, the constituents in Kenora who identify more with that party than the Conservatives would have a representative with whom they might feel more comfortable to address their concerns. So:

- To those who vote: You would in fact have two representatives, with possibly one of them sharing your political beliefs.

- To those who oppose PR on these grounds: Rural areas would in fact be more represented than they are now even though they already are more represented than urban areas out of concern for equity.

In short, it is important not to just look at the electoral map after an election, get blinded by huge expanses of a certain colour, and wonder why that party did not win more seats. For instance, seeing Nunavut in orange hides that, although it is 209,319 times bigger than Papineau, which is imperceptible on that map, it has less than one quarter of number of eligible voters in Papineau. Of course, Nuvanut/Papineau is the second most extreme examples I could take — Toronto Centre would be the most extreme — but all those sparsely populated huge ridings that cover the map can act as a trompe-l'œil. Saskatchewan and Manitoba: huge blocks on the map but, outside Regina, Saskatoon and Winnipeg, very few people to go to polling stations!

- "PR puts too much emphasis on parties. Those regional members would be accountable to their party, not their constituents."

- Not quite true, but at least this time you're bringing up a point worth discussing.

You are bringing up the valid debate about whether, on that second ballot, the list of candidates should be open or closed. An open-list ballot would be one on which you could pick an individual under a party heading. On a closed-list ballot, you would only vote for the party you support and, under the party's name, you would see the names of the individuals in the order they would be called upon to occupy a regional seat, as needed: the first person listed would get the first seat, the second would get the second, and so on.

You could reasonably argue — and I would tend to agree with you — that with a closed list, the parties would have elected their regional candidates, although let's not forget that, usually, candidates go through a nomination process, which means that parties already and always have a say on who will represent them. However, there would not necessarily be nefarious intentions behind the ordering of those candidates. It might be to ensure gender balance. It might be to reflect the region's cultural diversity. But yes, there could also be nefarious intentions, like a party really wanting to have a particular person elected but who, for whatever reason, might not be electable in a regular FPTP contest.

That is why I tend to prefer an open-list ballot. It would indirectly allow us to decide the order in which candidates would be called upon, and it would assuage your feeling (and mine) that we would not have elected those regional members — that they would have been imposed on us by the parties. The downside — and it is not a minor one — could be that not as many women or members of some significant community within a region would get elected. So:

- To those who vote: Based on this explanation, which type of list would you prefer: open or closed?

- To those who oppose PR on these grounds: That concern you raise can be addressed, as long as you don't just shut down the discussion with this argument.

Beyond deciding whether the lists should be open or closed, other considerations would have to include:

- Can a person appear simultaneously on a local and a regional ballot?

- Must the individuals appearing on a regional list be residents of the region, or could they appear on multiple regional lists?

- What would convince parties not to view regional lists as receptacles of what they consider second-tier candidates?

But now I am getting into the weeds of the system's design, and those are not arguments against PR.

- "Coalition governments would become the norm because no party could ever form a majority."

- And how exactly would that be a bad thing?

Clearly, Prime Minister Harper was successful during the 2008 non-confidence crisis to strip legitimacy from the notion of coalition, which are commonplace in extremely stable democracies like Germany. But if we are serious about reform, then it stands to reason that the rules governing non-confidence votes in our legislative assemblies would also need reforming. Those votes should be limited to the budget and when the government is found in contempt of parliament or is demonstrably corrupt. Those who have been elected would be obligated to respect how the electorate has asked to be represented. So:

- To those who vote: If coalitions can be made to work in other democracies, why not those in Canada?

- To those who oppose PR on these grounds: You just can't get enough power, right? Oh dear... Now get to work and make it work as we asked you to!

Yet we have a conservative columnist like the National Post's Kelly McParland insisting in this article from 2024  that even Germany's electoral system has become a mess in the 2020s, resorting to alarmist yet throw-away phrases like "the three-party government — typical of the sort of mishmash that often comes with proportional representation," and hammering on how there were 47 recognized parties in the 2021 federal election. McParland muses that the Liberal Party of Canada likely regretted having reneged on its promise to get rid of the first-past-the-post system, which he qualifies as the "old tried and true approach to voting" and "a system under which Canada has thrived for almost 160 years," conveniently omitting to mention that the Liberals wanted an even worse majoritarian system than FPTP, thereby insinuating that they wanted a PR system "involving party lists in place of individual candidates, mixed-member ballots, single transferable votes and other such exotic features ... even if it meant some members of Parliament being anointed by the party rather than the voter" (see above).

that even Germany's electoral system has become a mess in the 2020s, resorting to alarmist yet throw-away phrases like "the three-party government — typical of the sort of mishmash that often comes with proportional representation," and hammering on how there were 47 recognized parties in the 2021 federal election. McParland muses that the Liberal Party of Canada likely regretted having reneged on its promise to get rid of the first-past-the-post system, which he qualifies as the "old tried and true approach to voting" and "a system under which Canada has thrived for almost 160 years," conveniently omitting to mention that the Liberals wanted an even worse majoritarian system than FPTP, thereby insinuating that they wanted a PR system "involving party lists in place of individual candidates, mixed-member ballots, single transferable votes and other such exotic features ... even if it meant some members of Parliament being anointed by the party rather than the voter" (see above).

To be fair, he did not say that there are 47 parties in the Bundestag. However, he drops that number to imply that there could be, when in fact only nine parties are represented since 2021 because most parties cannot even come close to achieving the minimum threshold for representation, about which he makes no mention. There are currently fewer than 20 parties recognized by Elections Canada — there have been more at times, and as many as nine distinct political entities other than "Independent" could be counted in the Commons after the 1945 election — but even if the number of parties were to explode under a PR system, representation in the House is unlikely to be more diverse than what Germany has experienced, because its system is well designed, unlike Israel's or Italy's.

Along with the word coalition, the word compromise has fallen on the wayside and been made to seem dirty in a majoritarian electoral system. Yet all worthwhile social endeavours require compromise, and heterogenenous inputs often lead to better, more nuanced solutions. I am sure no elected politician in Germany ever said that forming and maintaining a coalition is easy; however, who said that governing is or should be easy?

- "We wouldn't know who won when we would go to bed on election night."

- So? As if that has never happened?

Worse things could happen than not knowing at bedtime on election night the exact number of seats each party will have. Yet I can already imagine the PR opponents on the night of a first PR election: "You see! You see! It's been two hours since the polls closed and we still don't know who won! What a mess, huh? This is all so confusing, right?" I mean, really? You seem addicted to instant gratification — or instant disappointment and outrage should you lose. Maybe you should get help for that.

Already, close local races have to go to a recount, and if some end up flipping to whomever was initially thought to be the second-place finisher, that would have an impact on the allocation of the regional seats. In other words, the proverbial dust may have to settle before we know the final counts, but that is not a sign that a PR system does not work or is confusing. It is simply that, as with many worthwhile endeavours, it can take a bit more time to do what is right. So:

- To those who vote: Give them time to count every vote and all will fall into place in the fullness of time.

- To those who oppose PR on these grounds: Would you please stop making things up?

The expectation that we should know all the winners a few hours after the polls close is, first, a modern phenomenon and, second, a by-product of more than 150 years of using majoritarian electoral systems that can provide decisive victories — even if a very large number of those victories were misaligned with what voters had expressed in the voting booth.

As the saying goes, "Haste makes waste." It is true that the determination of a government can happen fast under FPTP. For example, the evening of the 2022 Ontario general election, the medias declared a Progressive Conservative majority only 19 minutes after the polls closed! And then most people just as quickly moved on and accepted the majority/minority fiction that is based solely on the seat count, paying lip service to the fact that almost 60% opposed the government that had just been elected, and not realizing that the true winner of the election was Nobody. The waste in this case, as always, was presented as the "vote inefficiency" of the Greens and the Liberals — especially the Liberals — a concept wholly fabricated to excuse the biggest deficiency of FPTP. It is nonetheless shocking to see two parties receive almost the same number of votes, but the one that had 7,682 more getting nearly four times fewer seats.

Ontario Ontario |

43 → 2022 :: 2 Jun 2022 — Present —  Majority PC Majority PC

| Summary |

Government |

Opposition |

Unproductive votes |

| Party |

Votes |

Seats |

Party |

Votes |

Seats |

Party |

Votes |

| # |

% |

% |

# |

# |

% |

% |

# |

# |

% |

Parliament: 43  Majority Majority

Majority=63 Ab.Maj.: +21 G.Maj.: +42

Population [2022]: 14,996,014 (est.)

Eligible: 10,740,426 Particip.: 44.06%

Votes: 4,732,476 Unproductive: 276,196

Seats: 124 1 seat = 0.81%

↳ Elec.Sys.: FPTP: 124

↳ By acclamation: 0 (0.00%)

Plurality: Votes PC Seats PC

Plurality: ↳ +795,840 (+16.92%)

Plurality: ↳ Seats: +52 (+41.94%)

Position2: Votes LIB Seats NDP

|

Candidacies: 897 (✓ 124) m: 571 (✓ 77) f: 325 (✓ 46) x: 1 (✓ 1)

PC 124 NDP 124 LIB 121 GRN 124 IND 40 NBPO 123 OP 105 OTH 136

|

PC |

1,919,905 |

40.83 |

66.94 |

83 |

NDP

LIB

GRN

IND |

1,116,383

1,124,065

280,006

15,921 |

23.74

23.91

5.96

0.34 |

25.00

6.45

0.81

0.81 |

31

8

1

1 |

IND

NBPO

OP

OTH

REJ

ABS |

9,411

127,462

83,618

25,188

30,517

6,007,950 |

0.20

2.71

1.78

0.53

0.64

—— |

| LIB Won 23 fewer seats than the NDP which won 7,682 fewer votes.

IND One candidate officially ran as having no affiliation.

OTH → NOTA 28 LBT 16 PPO 13 FR 11 COMM 12 CO 11 OMP 17 CC 2 COR 3

OTH → PPPO 3 OPF 3 STSX 3 CENT 2 PPSN 2 NOP 2 PBP 2 CPJ 2 ERP 2 ALLI 2

|

|

Ontarians have become notorious in the 21st century for not turning out to vote provincially, but the all-time low reached in 2022 perhaps reflects that they consider the electoral system to be a waste of their time as it does not "listen" to them anyway. But the form of waste that everybody seems to understand is when the popular vote for one party should have reasonably yielded a few seats but did not, like when the Greens reached the respectable threshold of 6.8% of the votes nationwide in the 2008 federal election, not to mention that a very large proportion of the electorate didn't even bother to vote.

Canada Canada |

40 → 2008 :: 14 Oct 2008 — 1 May 2011 —  Minority CPC Minority CPC

| Summary |

Government |

Opposition |

Unproductive votes |

| Party |

Votes |

Seats |

Party |

Votes |

Seats |

Party |

Votes |

| # |

% |

% |

# |

# |

% |

% |

# |

# |

% |

Parliament: 40  Minority Minority

Majority=155 Ab.Maj.: -12 G.Maj.: -22

Population [2008]: 33,127,520 (est.)

Eligible: 23,617,343 Particip.: 58.98%

Votes: 13,929,093 Unproductive: 1,149,194

Seats: 308 1 seat = 0.32%

↳ Elec.Sys.: FPTP: 308

↳ By acclamation: 0 (0.00%)

Plurality: Votes CPC Seats CPC

Plurality: ↳ +1,575,884 (+11.39%)

Plurality: ↳ Seats: +66 (+21.43%)

Position2: Votes LIB Seats LIB

|

Candidacies: 1,601 (✓ 308) m: 1,155 (✓ 239) f: 446 (✓ 69) CPC 307 LIB 307 BQ 75 NDP 308 IND 71 GRN 303 OTH 230

|

CPC |

5,209,069 |

37.65 |

46.43 |

143 |

LIB

BQ

NDP

IND |

3,633,185

1,379,991

2,515,288

42,366 |

26.26

9.98

18.18

0.31 |

25.00

15.91

12.01

0.65 |

77

49

37

2 |

IND

GRN

OTH

REJ

ABS |

52,478

937,613

64,304

94,799

9,688,250 |

0.38

6.78

0.45

0.68

—— |

| OTH → CHP 59 ML 59 LBT 26 PCP 10 COMM 24 ACT 20 MP 8

OTH → NRHI 7 NLF 3 FPNP 6 AAEV 4 WLP 1 WBP 1 PPP 2

|

|

The waste can also be quantified in missed opportunities to notice the emerging trends hidden in plain sight in the numbers. For example, everyone seemed surprised when the Action démocratique du Québec formed the official opposition in the Québec National Assembly in 2007, forcing the Québec Liberal Party to form the first minority government in that province in nearly 130 years. However, the evidence of the ADQ's ascension was visible in the three previous general elections, which we would have seen coming if we had had a proportional system, not to mention that its supporters would have been heard sooner. Indeed, the ADQ's initial performance in 1994 could have been seen as a fluke like with the Equality Party in 1989 but, nine years later, the 2003 general election provided clear reasons to stop believing that was the case — except that everybody continued to focus only on the seat count.

Québec Québec |

35 → 1994 :: 12 Sep 1994 — 29 Nov 1998 —  Majority PQ Majority PQ

| Summary |

Government |

Opposition |

Unproductive votes |

| Party |

Votes |

Seats |

Party |

Votes |

Seats |

Party |

Votes |

| # |

% |

% |

# |

# |

% |

% |

# |

# |

% |

Parliament: 35  Majority Majority

Majority=63 Ab.Maj.: +15 G.Maj.: +29

Population [1994]: 7,184,599 (est.)

Eligible: 4,893,465 Particip.: 81.63%

Votes: 3,994,628 Unproductive: 250,722

Seats: 125 1 seat = 0.80%

↳ Elec.Sys.: FPTP: 125

↳ By acclamation: 0 (0.00%)

Plurality: Votes PQ Seats PQ

Plurality: ↳ +13,212 (+0.34%)

Plurality: ↳ Seats: +30 (+24.00%)

Position2: Votes QLP Seats QLP

|

Candidacies: 682 (✓ 125) m: 541 (✓ 102) f: 141 (✓ 23) PQ 125 QLP 125 ADQ 80 NPDQ 41 EP 18 IND 68 OTH 225

|

PQ |

1,752,298 |

44.74 |

61.60 |

77 |

QLP

ADQ |

1,739,086

252,522 |

44.40

6.45 |

37.60

0.80 |

47

1 |

NPDQ

EP

IND

OTH

REJ

ABS |

33,703

11,671

66,221

61,375

77,752

898,837 |

0.86

0.30

1.69

1.58

1.95

—— |

| ADQ First general election for this party.

OTH → NLP 103 SOV 19 GPQ 11 LMP 10 C 10 CWCQ 18 DQ 11 QIP 11 EPQ 9 ML 13 COMM 10

|

|

36 → 1998 :: 30 Nov 1998 — 13 Apr 2003 —  Majority PQ Majority PQ

| Summary |

Government |

Opposition |

Unproductive votes |

| Party |

Votes |

Seats |

Party |

Votes |

Seats |

Party |

Votes |

| # |

% |

% |

# |

# |

% |

% |

# |

# |

% |

Parliament: 36  Majority Majority

Majority=63 Ab.Maj.: +14 G.Maj.: +27

Population [1998]: 7,290,497 (est.)

Eligible: 5,254,482 Particip.: 78.32%

Votes: 4,115,169 Unproductive: 118,435

Seats: 125 1 seat = 0.80%

↳ Elec.Sys.: FPTP: 125

↳ By acclamation: 0 (0.00%)

Plurality: Votes QLP Seats PQ

Plurality: ↳ +27,618 (+0.68%)

Plurality: ↳ Seats: -28 (-22.40%)

Position2: Votes PQ Seats QLP

|

Candidacies: 657 (✓ 125) m: 514 (✓ 96) f: 143 (✓ 29) PQ 124 QLP 125 ADQ 125 PSD 97 EP 24 IND 38 OTH 124

|

PQ |

1,744,240 |

42.87 |

60.80 |

76 |

QLP

ADQ |

1,771,858

480,636 |

43.55

11.81 |

38.40

0.80 |

48

1 |

PSD

EP

IND

OTH

REJ

ABS |

24,103

12,543

7,418

27,680

46,691

1,139,313 |

0.59

0.31

0.18

0.67

1.13

—— |

The electoral system brought the "wrong winner" at the head of the seat count.

PSD Formed after the 1994 general election from the NDPQ.

OTH → BPQ 24 NLP 35 RAP 1 ML 24 QIP 20 COMM 20

COMM Last general election for this party before the merger of its political wing with l'Union des forces progressistes in 2002.

|

|

37 → 2003 :: 14 Apr 2003 — 25 Mar 2007 —  Majority QLP Majority QLP

| Summary |

Government |

Opposition |

Unproductive votes |

| Party |

Votes |

Seats |

Party |

Votes |

Seats |

Party |

Votes |

| # |

% |

% |

# |

# |

% |

% |

# |

# |

% |

Parliament: 37  Majority Majority

Majority=63 Ab.Maj.: +14 G.Maj.: +27

Population [2003]: 7,471,775 (est.)

Eligible: 5,490,363 Particip.: 70.56%

Votes: 3,874,143 Unproductive: 147,548

Seats: 125 1 seat = 0.80%

↳ Elec.Sys.: FPTP: 125

↳ By acclamation: 0 (0.00%)

Plurality: Votes QLP Seats QLP

Plurality: ↳ +487,282 (+12.74%)

Plurality: ↳ Seats: +31 (+24.80%)

Position2: Votes PQ Seats PQ

|

Candidacies: 644 (✓ 125) m: 470 (✓ 87) f: 174 (✓ 38) QLP 125 PQ 125 ADQ 125 UFP 73 EP 21 IND 36 OTH 139

|

QLP |

1,758,200 |

45.96 |

60.80 |

76 |

PQ

ADQ |

1,270,918

697,477 |

33.22

18.23 |

36.00

3.20 |

45

4 |

UFP

EP

IND

OTH

REJ

ABS |

40,319

4,051

8,611

45,653

48,914

1,616,220 |

1.05

0.11

0.23

1.19

1.26

—— |

| UFP Formed in June 2002 from the Party for Socialist Democracy and other leftist parties.

OTH → BPQ 56 GPQ 36 QCDP 24 ML 23

BPQ Best result for this party (0.60%).

|

|

38 → 2007 :: 26 Mar 2007 — 7 Dec 2008 —  Minority QLP Minority QLP

| Summary |

Government |

Opposition |

Unproductive votes |

| Party |

Votes |

Seats |

Party |

Votes |

Seats |

Party |

Votes |

| # |

% |

% |

# |

# |

% |

% |

# |

# |

% |

Parliament: 38  Minority Minority

Majority=63 Ab.Maj.: -15 G.Maj.: -29

Population [2007]: 7,674,385 (est.)

Eligible: 5,630,567 Particip.: 71.23%

Votes: 4,010,683 Unproductive: 347,070

Seats: 125 1 seat = 0.80%

↳ Elec.Sys.: FPTP: 125

↳ By acclamation: 0 (0.00%)

Plurality: Votes QLP Seats QLP

Plurality: ↳ +89,261 (+2.24%)

Plurality: ↳ Seats: +7 (+5.60%)

Position2: Votes ADQ Seats ADQ

|

Candidacies: 679 (✓ 125) m: 467 (✓ 93) f: 212 (✓ 32) QLP 125 ADQ 125 PQ 125 QS 123 IND 28 OTH 153

|

QLP |

1,313,664 |

33.08 |

38.40 |

48 |

ADQ

PQ |

1,224,403

1,125,546 |

30.84

28.35 |

32.80

28.80 |

41

36 |

QS

IND

OTH

REJ

ABS |

144,414

4,490

158,088

40,078

1,619,884 |

3.64

0.11

3.98

1.00

—— |

| First minority government in more than 120 years.

QS Formed on 4 February 2006 from the Union des forces progressistes and other leftist parties.

OTH → GPQ 108 ML 24 BPQ 9 QCDP 12

GPQ Best result for this party (3.85%).

|

|

However, following the 2008 election, the ADQ returned to the Assembly as a non-recognized opposition group and underrepresented compared to its share of the popular vote.

Québec Québec |

39 → 2008 :: 8 Dec 2008 — 3 Sep 2012 —  Majority QLP Majority QLP

| Summary |

Government |

Opposition |

Unproductive votes |

| Party |

Votes |

Seats |

Party |

Votes |

Seats |

Party |

Votes |

| # |

% |

% |

# |

# |

% |

% |

# |

# |

% |

Parliament: 39  Majority Majority

Majority=63 Ab.Maj.: +4 G.Maj.: +7

Population [2008]: 7,740,347 (est.)

Eligible: 5,738,811 Particip.: 57.43%

Votes: 3,295,914 Unproductive: 134,141

Seats: 125 1 seat = 0.80%

↳ Elec.Sys.: FPTP: 125

↳ By acclamation: 0 (0.00%)

Plurality: Votes QLP Seats QLP

Plurality: ↳ +224,295 (+6.91%)

Plurality: ↳ Seats: +15 (+12.00%)

Position2: Votes PQ Seats PQ

|

Candidacies: 651 (✓ 125) m: 448 (✓ 88) f: 203 (✓ 37) QLP 125 PQ 125 ADQ 125 QS 122 IND 30 OTH 124

|

QLP |

1,366,046 |

42.08 |

52.80 |

66 |

PQ

ADQ

QS |

1,141,751

531,358

122,618 |

35.17

16.37

3.78 |

40.80

5.60

0.80 |

51

7

1 |

IND

OTH

REJ

ABS |

6,506

78,054

49,581

2,442,897 |

0.20

2.40

1.50

—— |

OTH → GPQ 80 INP 19 ML 23 DPQ 1 QRP 1

|

|

Maybe the people of Québec did not like what they saw from the ADQ once it finally had a significant presence in the National Assembly, but FPTP dished out a harsher punishment on the ADQ than what the electorate had prescribed. Yet one has to wonder if the Québécois might have reached their verdict on the ADQ sooner under PR? Or if, conversely, the ADQ might have had the opportunity to develop its political muscles and taken root in the Assembly had it had from the beginning a number of seats commensurate to its popular support? But certainly the course of our political history would have been and would be different if we had a PR electoral system.

In short, perhaps the only virtues of FPTP are that it is easy to understand and fast at producing results. However, those quickly-obtained results are misleading in the long term, only serve the winners' immediate interests, and eventually lead to voters disengaging from the process, as evidenced by the Ontario general elections of the last two decades. I would rather go to bed on election night knowing that my vote really mattered.

- "I think that those who want PR have a hidden agenda. Frankly, I think they want more than they deserve!"

- You mean like you've been getting for the last 150+ years? The joke goes like this...

A billionaire, a working man, and an immigrant are around a table on which there are 10 cookies. The billionaire takes 9 of them and then whispers to the working man, "That guy's gonna steal your cookie."

Substitute "a billionaire" with a party leader, "a working man" with a supporter of that party, and "an immigrant" with a non-supporter of that party. Over all these years of using majoritarian electoral systems, members of the political class have become accustomed to the idea that if they play their cards right, they could have near absolute power by winning more seats in their legislative assembly than they would if a fair voting system were in place. The "winner takes all" mentality, which prevails within voting systems like FPTP, leads to a mindset whereby "Anyone who is not like me" (or in my party) "does not deserve a place in the legislature."

The fact is that with FPTP, just like when one plays cards, pure luck has as much a role in obtaining that "desirable" outcome of a majority as does crafting policies that will appeal to the electorate. But then it seems that when the label "majority" gets fixed onto a government, the winners get confused. They start to think that everybody is on their side. And that way of thinking can, in time, lead to hubris and catastrophic political decisions. My conclusion after years of observation is that the political class desire majority governments, while the people want good governance and to be heard by their elected officials, and the former is not the prescription for the latter.

I do not wish to pick a fight with Québec sovereignists, but I posit that had the electoral system been proportional in 1976 and 1994, the Parti Québécois might have read the results differently and thought twice about attempting their referendums on sovereignty. I believe, as I examine these numbers, that the 1976 general election spoke as much about the Liberal Party's wear of power as it did about a considerable number of people believing that Québec should become an independent nation, while the 1994 event might also have been speaking about wear of power but was mostly coloured by a decade of disappointing constitutional talks that came to naught. Le beau risque had failed...

Québec Québec |

31 → 1976 :: 15 Nov 1976 — 12 Apr 1981 —  Majority PQ Majority PQ

| Summary |

Government |

Opposition |

Unproductive votes |

| Party |

Votes |

Seats |

Party |

Votes |

Seats |

Party |

Votes |

| # |

% |

% |

# |

# |

% |

% |

# |

# |

% |

Parliament: 31  Majority Majority

Majority=56 Ab.Maj.: +16 G.Maj.: +32

Population [1976]: 6,234,445

Eligible: 4,020,608 Particip.: 85.33%

Votes: 3,430,952 Unproductive: 107,385

Seats: 110 1 seat = 0.91%

↳ Elec.Sys.: FPTP: 110

↳ By acclamation: 0 (0.00%)

Plurality: Votes PQ Seats PQ

Plurality: ↳ +255,295 (+7.59%)

Plurality: ↳ Seats: +45 (+40.91%)

Position2: Votes QLP Seats QLP

|

Candidacies: 556 (✓ 110) m: 510 (✓ 105) f: 46 (✓ 5) PQ 110 QLP 110 UN 108 SCRQ 109 OTH 75 NPDQ 21 IND 23

|

PQ |

1,390,351 |

41.37 |

64.55 |

71 |

QLP

UN

SCRQ

OTH |

1,135,056

611,666

155,451

31,043 |

33.78

18.20

4.63

0.92 |

23.64

10.00

0.91

0.91 |

26

11

1

1 |

OTH

NPDQ

IND

REJ

ABS |

20,787

3,080

13,072

70,446

589,656 |

0.62

0.09

0.39

2.05

—— |

| PQ First government formed by this party.

OTH → PNP 36 (✓ 1) DA 13 COMM 14 QWP 12

PNP Ephemeral party (1976–79) of social credit tendency.

|

|

35 → 1994 :: 12 Sep 1994 — 29 Nov 1998 —  Majority PQ Majority PQ

| Summary |

Government |

Opposition |

Unproductive votes |

| Party |

Votes |

Seats |

Party |

Votes |

Seats |

Party |

Votes |

| # |

% |

% |

# |

# |

% |

% |

# |

# |

% |

Parliament: 35  Majority Majority

Majority=63 Ab.Maj.: +15 G.Maj.: +29

Population [1994]: 7,184,599 (est.)

Eligible: 4,893,465 Particip.: 81.63%

Votes: 3,994,628 Unproductive: 250,722

Seats: 125 1 seat = 0.80%

↳ Elec.Sys.: FPTP: 125

↳ By acclamation: 0 (0.00%)

Plurality: Votes PQ Seats PQ

Plurality: ↳ +13,212 (+0.34%)

Plurality: ↳ Seats: +30 (+24.00%)

Position2: Votes QLP Seats QLP

|

Candidacies: 682 (✓ 125) m: 541 (✓ 102) f: 141 (✓ 23) PQ 125 QLP 125 ADQ 80 NPDQ 41 EP 18 IND 68 OTH 225

|

PQ |

1,752,298 |

44.74 |

61.60 |

77 |

QLP

ADQ |

1,739,086

252,522 |

44.40

6.45 |

37.60

0.80 |

47

1 |

NPDQ

EP

IND

OTH

REJ

ABS |

33,703

11,671

66,221

61,375

77,752

898,837 |

0.86

0.30

1.69

1.58

1.95

—— |

| ADQ First general election for this party.

OTH → NLP 103 SOV 19 GPQ 11 LMP 10 C 10 CWCQ 18 DQ 11 QIP 11 EPQ 9 ML 13 COMM 10

|

|

Indeed, I am left wondering if both René Lévesque and Jacques Parizeau were on an electoral "adrenaline rush." Lévesque's might have been fuelled by forming a government only eight years after his party was founded, while Parizeau's was clearly amplified by the failures of the Meech and Charlottetown Accords. (I mean, look at that! In 1994, the PQ's 24% seat plurality over the PLQ rested on the weight of a vote plurality of only 0.34%!)

Nevertheless, it's as though both men only took into account their seat plurality and the fact they controlled more than 60 percent of the National Assembly, so surely they could pull it off! But if their representation in the legislature had been closer to what they obtained in the popular vote during the elections that swept them to power, would they not have had to concede that the "winning conditions" were not quite there yet? Did their electoral majority "adrenaline rush" make them too confident and, ultimately, lead them to what was (for them) a catastrophe?

I could find many similar examples from the 407 other partisan general elections recorded in PoliCan, but with those I am risking getting subjective and partisan as to what constitutes a "catastrophe." For some, the NDP's "Social Contract" or the Conservatives' "Common Sense Revolution" in Ontario in the 1990s were catastrophes but not for others. The manner in which the federal Liberals eliminated the deficit between 1993 and 2004 was a catastrophe for some, but others believe to this day that it just had to be done. This list could go on.

However, I feel at ease to make this one observation: the greater a party's seat plurality or government majority, the more that party has free rein and, given that so few governments have been formed with a real majority of those who voted, the more likely the real majority will be upset and feel powerless during the course of that party's mandate. It is infuriating to hear a government brag that it has the majority of Canadians or Manitobans or New Brunswickers or whoever on its side when that assertion is based on its inflated parliamentary majority that is backed by as few as 38% of those who voted!

But the saying that comes to my mind as I think about the above Québec examples is, "Be careful what you wish for." Wishing for a legislative majority, and then getting it, can sometimes lead to political and tactical errors. And the simple fact is that everyone, within reason, is deserving of representation. So:

- To those who vote: Demand to be represented as you have asked, and banish the thought that compromise is a bad thing.

- To those who oppose PR on these grounds: Your slip is more than showing and you need to put your sense of entitlement in check!

For indeed, in a healthy democracy, governing needs to be in tune with how the governed wish to be governed. If anyone has a "hidden agenda," that would be those who benefitted from and therefore wish to preserve the unfair electoral system that has been chosen for us. Their agenda — the one they are hiding from you — is that they want to keep gaming the system so that they can satisfy their base which, almost always, constitutes a minority of the electorate.

Many of us gasp with horror and clutch our pearls when somebody in the room says, "Meh... my vote doesn't count..." We rail when we see only 44% of Ontarians vote, as was the case in the 2022 general election. We pull our hair trying to think of ways of getting people to exercise their franchise, especially young people. We disapprove when we hear others say that all political parties are the same. And we scratch our head after an election in which there's a huge disconnect between vote and seat percentages.

I have long held that cynicism towards the political class, alone, is not the reason why so many refuse to engage in the political process. After pouring through all the numbers, seeing how hopeless one can feel wanting to vote for Party X when Party Y has won every election in a riding for the last 60 years — I live in such ridings, provincially and federally — and hearing so much talk about how and why the system is broken, I have to admit they a good reason to have become disaffected.

Our electoral system is indeed broken. It is tone deaf. It marginalizes legitimate points of view. It is predicated on exclusion rather than inclusion.

What if the system were designed in such a way that voting Green in Yarmouth or Liberal in Camrose would not be pointless? That it could hear those more quiet voices, provided they are in sufficient numbers? That it would not completely exclude some from the conversation?

Proportional representation could do that, and we would be better as a society for it. It would not be a panacea, but it would certainly not repel people from the polls. In fact, to the contrary, it could help restore confidence in our political system. Besides, doing the same thing over and over and wishing that everything will eventually fix itself is just magical thinking!

Isn't the experience of more than 150 years enough evidence that our problem isn't just going to go away on its own?

But in order for us to succeed in effecting change...

© 2019, 2024 :: PoliCan.ca (

Maurice Y. Michaud)

Pub.: 9 May 2022 23:15

Rev.: 21 Jan 2024 19:28

Not surprisingly, those who have never studied electoral systems nor looked as I have, without bias, at the results of all the elections ever held in Canada tend to opine freely but very superficially on the matter of electoral reform. I offer as evidence the comments section of this article that appeared on CBC News

Not surprisingly, those who have never studied electoral systems nor looked as I have, without bias, at the results of all the elections ever held in Canada tend to opine freely but very superficially on the matter of electoral reform. I offer as evidence the comments section of this article that appeared on CBC News  shortly after the 2015 federal election. Just as everyone suddenly seemed to become epidemiologists during the COVID-19 pandemic, we tend to assume that we know the minutiae of our electoral system because we all know how to cast a ballot. But, in fairness, I need to remind myself that, along with Éric Grenier and Philippe J. Fournier, I am probably one of the few Canadians who is crazy enough to have recorded and poured over all those results in detail — with apologies to Éric and Philippe for somehow suggesting that they are crazy, which they are not!

shortly after the 2015 federal election. Just as everyone suddenly seemed to become epidemiologists during the COVID-19 pandemic, we tend to assume that we know the minutiae of our electoral system because we all know how to cast a ballot. But, in fairness, I need to remind myself that, along with Éric Grenier and Philippe J. Fournier, I am probably one of the few Canadians who is crazy enough to have recorded and poured over all those results in detail — with apologies to Éric and Philippe for somehow suggesting that they are crazy, which they are not! , can simplify the argument too much. They only look at the percentages of the popular vote across the jurisdiction and translate that percentage into number of seats. Except Canada is a big country with extreme regional differences politically. Try finding a Green Party supporter in Newfoundland or a Liberal supporter in Fort McMurray... and I wish you good luck with that!

, can simplify the argument too much. They only look at the percentages of the popular vote across the jurisdiction and translate that percentage into number of seats. Except Canada is a big country with extreme regional differences politically. Try finding a Green Party supporter in Newfoundland or a Liberal supporter in Fort McMurray... and I wish you good luck with that! is particularly guilty of that sin. Juxtapose someone like him to Chantal Hébert, who, granted, is not a polemicist but calls the good and the bad shots by whomever, regardless of their political stripe, and never gives away her own political leanings even though we might suspect what they are, or more likely aren't. On the bright side, if the arguments of opponents of PR have holes big enough to drive a truck through them, then making the case for it should be easier as long as their lack of credibility can be made plain for everyone to see. So let's talk about their flimsy arguments — except Christian Dufour's, since his slip is not just showing; his entire outfit has fallen off and he is already embarrassing himself parading nude.

is particularly guilty of that sin. Juxtapose someone like him to Chantal Hébert, who, granted, is not a polemicist but calls the good and the bad shots by whomever, regardless of their political stripe, and never gives away her own political leanings even though we might suspect what they are, or more likely aren't. On the bright side, if the arguments of opponents of PR have holes big enough to drive a truck through them, then making the case for it should be easier as long as their lack of credibility can be made plain for everyone to see. So let's talk about their flimsy arguments — except Christian Dufour's, since his slip is not just showing; his entire outfit has fallen off and he is already embarrassing himself parading nude.

2016 Angus Maguire via Interaction Institute for Social Change — Fair trade

2016 Angus Maguire via Interaction Institute for Social Change — Fair trade that even Germany's electoral system has become a mess in the 2020s, resorting to alarmist yet throw-away phrases like "the three-party government — typical of the sort of mishmash that often comes with proportional representation," and hammering on how there were 47 recognized parties in the 2021 federal election. McParland muses that the Liberal Party of Canada likely regretted having reneged on its promise to get rid of the first-past-the-post system, which he qualifies as the "old tried and true approach to voting" and "a system under which Canada has thrived for almost 160 years," conveniently omitting to mention that the Liberals wanted an even worse majoritarian system than FPTP, thereby insinuating that they wanted a PR system "involving party lists in place of individual candidates, mixed-member ballots, single transferable votes and other such exotic features ... even if it meant some members of Parliament being anointed by the party rather than the voter" (see above).

that even Germany's electoral system has become a mess in the 2020s, resorting to alarmist yet throw-away phrases like "the three-party government — typical of the sort of mishmash that often comes with proportional representation," and hammering on how there were 47 recognized parties in the 2021 federal election. McParland muses that the Liberal Party of Canada likely regretted having reneged on its promise to get rid of the first-past-the-post system, which he qualifies as the "old tried and true approach to voting" and "a system under which Canada has thrived for almost 160 years," conveniently omitting to mention that the Liberals wanted an even worse majoritarian system than FPTP, thereby insinuating that they wanted a PR system "involving party lists in place of individual candidates, mixed-member ballots, single transferable votes and other such exotic features ... even if it meant some members of Parliament being anointed by the party rather than the voter" (see above). Ontario

Ontario Majority

Majority Canada

Canada Minority

Minority Québec

Québec Majority

Majority Majority PQ

Majority PQ  Majority

Majority Majority QLP

Majority QLP  Majority

Majority Minority QLP

Minority QLP  Minority

Minority Québec

Québec Majority

Majority Québec

Québec Majority

Majority Majority PQ

Majority PQ  Majority

Majority